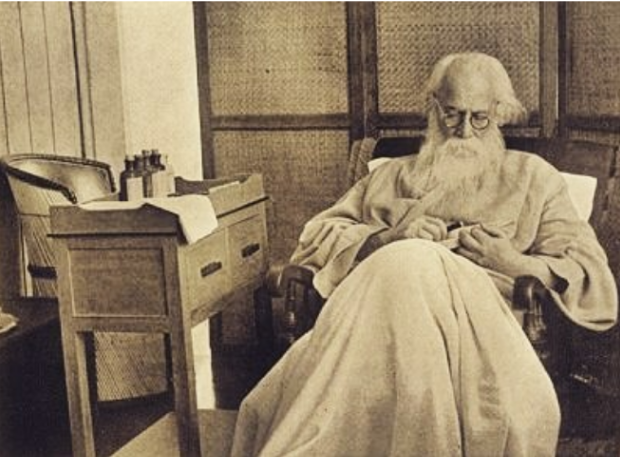

Baishe Srabon: Remembering the last few days of the Laureate Tagore

Blog by: Parthib Banerjee

Honouring the passings of incredible people is certainly not a customary Bengali social practice. There is, in any case, one exemption; the death of Rabindranath Tagore on August 7, 1941, or what in the Bengali schedule was Baishe Srabon.

Rabindranath grumbled of a few actual diseases since he was in his fifties. A portion of these impacted his well-being genuinely as he became old. In September 1940, while he was travelling to Kalimpong, his condition decayed, and he wanted clinical mediation. It was recognized that he was experiencing entanglements emerging from an extended prostate. In July 1941, The trio of exclusive well-wishers and friends of Tagore, Dr Lalit Banerjee, Dr Indu Bose & Dr B. C.Roy, decided that medical procedure was essential to save the writer. Thus, Rabindranath reached his home in Jorasanko, where Dr Lalitmohan Banerjee led the medical practice on July 30.

It was felt that Rabindranath was close to his end. Standard clinical notices were distributed in significant English and Bengali dailies of the times and were followed restlessly by individuals. At last, on Baishe Srabon, when fresh insight about his dying — affirmed by the specialists to have happened at 12.13 pm — contacted them, a vast horde of grievers went into a free-for-all as though it had smothered overpowering melancholy while sitting tight for the occasion. After four months, his child Rathindranath Tagore recalled this emission of aggregate grieving as an outflow of aggregate despair: ‘The burial service itself was a most phenomenal and unbelievable experience — millions with over the top enthusiasm attempting to get a brief look at their cherished one and acting in a curiously unreasonable way as their psychological equilibrium had snapped.’

Nirmal Kumari Mahalanobis, the spouse of Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis, also recalled the furious and intrusive requests of the group that had burst into the Jorasanko chateau to triumph ultimately a last look at the body of their cherished writer. Jams had broken into the room where relatives and a couple of close partners were washing and blessing Rabindranath’s body for the last rituals. The group viewed a demonstration of infringement and added to profaning as a declaration of holy regard. The tone of misery didn’t change much even as individuals followed the funeral car, mainly designed by the craftsman Nandalal Bose of Kala Bhavana, that helped the body in a parade through the city to the Neemtala crematorium in Kolkata.

In the mediating eighty years, Baishe Srabon has quit being a simple date in the Bengali schedule for the informed working class Bengali. It has turned into a metonym for aggregate grieving, an event for therapy that started with the passing of Rabindranath, who has moulded a lot of their social and social personality — in life as much as in death.

The portion underneath is from Tagore’s University: A History of the Visva-Bharti (1921-1961)

Nonappearance, Uneasiness, Palpitation

On September 21 1941, an assemblage had accumulated in the Chhatimtala, a wood of chhatim trees. The chhatim’s leaves were (and keep on being) of extraordinary emblematic worth in Visva-Bharati’s yearly meeting. It was standard for functions, particularly those which denoted the more formal and grave occasions in the schedule of Visva-Bharati, underneath Chhatimtala, given its relationship with the hallowed. A little white marble petitioning God seat situated there had a plaque bearing an engraving in Bengali which, deciphered, read: “He is the solace of my heart, the delight of my psyche and the tranquillity of my spirit.”

This was where the remembrance administration for Rabindranath Tagore was led on August 17 1941, ten days after his passing, with the reciting of Vedic songs and refrains from the Rigveda. Vidhusekhar Bhattacharya – who had officially surrendered yet whose connections with the organization had never snapped – and Kshitimohan Sen played out the customs. During this event, Kshitimohan appeared detached, enveloped by thought, as his eyes cleared over the gathering in the Chhatimtala. A unique community of the Parishat was before long met to give proper respect to Rabindranath Tagore and examine the manners by which the organization and local area would find a sense of peace with the misfortune. Charu Chandra Dutt, Upacharya of Visva-Bharati, enunciated the feeling of nonattendance:

We, labourers of the Visva-Bharati, were till now protected in the defensive shadow of a mountain. He watched us against all buffetings of adversity to empower us to do our piece of work unencumbered. Now that he is no more, we should oppose the overwhelming power of the disruptions that might come in ongoing days . . . exclusively, to maintain the significance of this foundation which he has accomplished such a great deal to cultivate. It is valid that the brunt of the work falls on the leader, yet why not let us guarantee that we are ready to share their work at this essential point?

As Kshitimohan paid attention to Charuchandra, it struck him how troublesome the way forward was probably going to be. Respected as the kulasthabir (local area senior), Kshitimohan was known as a wise man who pondered matters profoundly before arriving at a choice. He had, step by step, become an essential individual from numerous managerial and scholarly advisory groups and was liable for the running of Vidya Bhavana. He reviewed how a pall of melancholy had wrapped the ashram since the twenty-second day of Sravana, the day when Gurudev died. However, the intellectual and different exercises of the foundation went on as expected in this way. The soul of the ashram could at no point ever go back in the future.

Over a month after the writer’s demise, the faint shadow of aggregate misery and grieving appeared to be blurring – if at any time so marginally. Maybe this was connected to the adjustment of seasons; the rainstorm was concluding with the smells of green mango, jacaranda, sal, mahua, etc., established over a very long time in the ashram premises – had a lush green shade. Sarat, early pre-winter, a glamorous and transitory season in the district, had started. The days were as yet blistering; however, the mornings and nights were agreeably cool.

Rabindranath had been a relentless author of epistles, speaking with loved ones from each edge of the globe and better places inside the country. In a portion of his letters, he elucidated his underlying thoughts while setting up the Brahmacharyashram and, later, Visva-Bharati. Some of the time, he set down rules for the working of its different organizations. He gave ideas on the educational plan of dialects and culture, particularly for the exploration program of Vidya Bhavana. He elaborates on the significance of Visva-Bharati in fierce social and political times; he composed movingly, in composition studded with similitudes, of how he had considered Visva-Bharati as a counter to the powers which appeared to him keen on obliterating humankind. Presently there would be no letters home, no homecoming for the one who resembled an unbound bird, flying much of the time out into the dark blue and getting back to his home.

0 Comments